Background

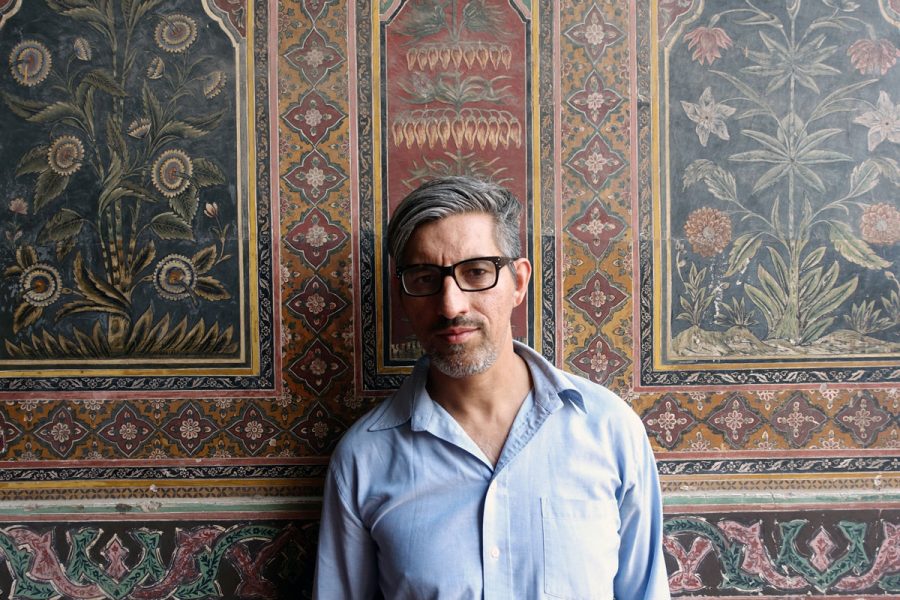

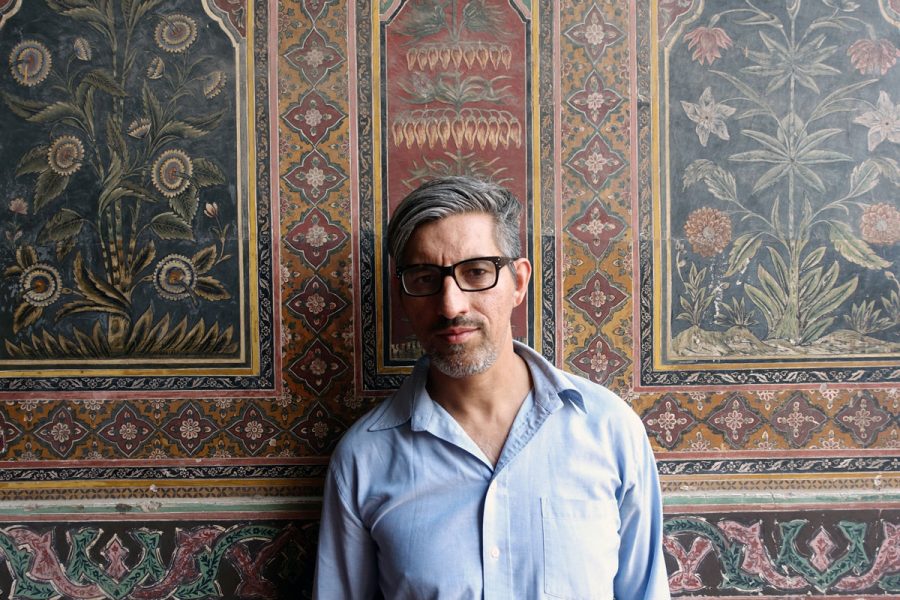

Statement by Wajid Yaseen – Director of the Tape Letters project

“Cassette tapes were an inexpensive and easy way to access and share music when I was growing up in Manchester in the 1970s, and the reaction by the music industry to home recordings on blank tapes made the illicit act of recording music off the radio or from records all the more exciting.

Like most kids, we were interested in pop music, but also rock, and new styles of electronic music coming mainly from the US (Electro and early Hip Hop) and mainland European – Jean Michel Jarre and his operatic electronica, Kraftwerk etc). Cassettes containing this music would invariably be scattered around the home, but cassettes owned by my parents would be lying around too. Their cassettes contained Ghazals (poems centring on themes of love and separation), Qawwalis (devotional Sufi music), and Naats (devotional hymns).

My father had a keen interest in Naats and very often was invited to sing in people’s homes or at public ceremonies as the British Pakistani communities in various towns and cities in the north of England settled and grew.

The development of cassette technology and the ability to record at home allowed him to share his singing within his community in an entirely new way, and a burgeoning cassette tape culture grew around his Naat singing. He passed away in 2001 but my family still have a number of these cassette recordings of him singing his Naats, and it was whilst I was rummaging around in my mum’s house a few years ago wanting to hear his voice again that I found a number of other cassettes.

The labels and inner sleeves contained scribbled messages to distant relatives and discovering them in my mum’s drawer triggered childhood memories of when I myself was coerced into recording messages to distant relatives of my own. I knew there and then that these other cassettes I’d found wouldn’t contain singing or music, but rather monologues and private messages, and by asking around, I found out that it wasn’t just my own family that used them in this way.

Given the intensely private nature of the contents of the cassettes and the obsolescence of the medium itself, I didn’t think we’d find or be given access to many of these ‘tape letters’ and indeed they are pretty rare, and when they do exist many people are understandably reluctant to share them. Nevertheless, the project team and I have managed to secure around twenty cassettes from a number of different families, and have interviewed over fifty individuals living in the UK and in Pakistan, providing us with a rich insight into this practice of recording messages on tape.

I’ve been fascinated with sound, music, and active listening since I can remember, and as I was handling these newfound cassettes in my mother’s home, I realised that these cheap pieces of plastic and magnetic tape were perfect sonographic snapshots of the time.

Reflecting and analysing them has been a sort of ‘sonic archaeology’ and the TAPE LETTERS project has provided me with an insight not only into the migratory experience of my immediate family, but also into the wider issues of migration and identity, into how language mutates and drifts, and has revealed the ingenious ways in which people adapt technology to suit their needs wherever they are, and wherever they’re from.”

Wajid Yaseen

Statement by Wajid Yaseen – Director of the Tape Letters project

“Cassette tapes were an inexpensive and easy way to access and share music when I was growing up in Manchester in the 1970s, and the reaction by the music industry to home recordings on blank tapes made the illicit act of recording music off the radio or from records all the more exciting.

Like most kids, we were interested in pop music, but also rock, and new styles of electronic music coming mainly from the US (Electro and early Hip Hop) and mainland European – Jean Michel Jarre and his operatic electronica, Kraftwerk etc). Cassettes containing this music would invariably be scattered around the home, but cassettes owned by my parents would be lying around too. Their cassettes contained Ghazals (poems centring on themes of love and separation), Qawwalis (devotional Sufi music), and Naats (devotional hymns).

My father had a keen interest in Naats and very often was invited to sing in people’s homes or at public ceremonies as the British Pakistani communities in various towns and cities in the north of England settled and grew.

The development of cassette technology and the ability to record at home allowed him to share his singing within his community in an entirely new way, and a burgeoning cassette tape culture grew around his Naat singing. He passed away in 2001 but my family still have a number of these cassette recordings of him singing his Naats, and it was whilst I was rummaging around in my mum’s house a few years ago wanting to hear his voice again that I found a number of other cassettes.

The labels and inner sleeves contained scribbled messages to distant relatives and discovering them in my mum’s drawer triggered childhood memories of when I myself was coerced into recording messages to distant relatives of my own. I knew there and then that these other cassettes I’d found wouldn’t contain singing or music, but rather monologues and private messages, and by asking around, I found out that it wasn’t just my own family that used them in this way.

Given the intensely private nature of the contents of the cassettes and the obsolescence of the medium itself, I didn’t think we’d find or be given access to many of these ‘tape letters’ and indeed they are pretty rare, and when they do exist many people are understandably reluctant to share them. Nevertheless, the project team and I have managed to secure around twenty cassettes from a number of different families, and have interviewed over fifty individuals living in the UK and in Pakistan, providing us with a rich insight into this practice of recording messages on tape.

I’ve been fascinated with sound, music, and active listening since I can remember, and as I was handling these newfound cassettes in my mother’s home, I realised that these cheap pieces of plastic and magnetic tape were perfect sonographic snapshots of the time.

Reflecting and analysing them has been a sort of ‘sonic archaeology’ and the TAPE LETTERS project has provided me with an insight not only into the migratory experience of my immediate family, but also into the wider issues of migration and identity, into how language mutates and drifts, and has revealed the ingenious ways in which people adapt technology to suit their needs wherever they are, and wherever they’re from.”

Wajid Yaseen