About

Tape Letters

The Tape Letters project shines light on the practice of recording and sending messages on cassette tape as a mode of communication by Pakistanis who migrated and settled in the UK between 1960-1980.

Drawing directly both from first-hand interviews and from the informal and intimate conversations on the cassettes themselves, the project seeks to unearth, archive and re/present a portrait of this method of communication, as practised mainly by Potwari-speaking members of the British-Pakistani community, commenting on their experiences of migration and identity, commenting on the unorthodox use of cassette tape technology, and commenting on the language used in the recordings.

The project focuses on Pothwari primarily because the majority of cassettes acquired and the majority of the interviews undertaken have been in this language, but also because it is solely a spoken language and its capture on cassette tape provides some insights into the traditions of an oral culture.

Cassette culture

Cassette tapes were developed by the Dutch technology company Phillips in 1963 originally for dictation machines, but with rapid improvements in audio fidelity, they became hugely popular as a format for pre-recorded music. They were also available as ‘blank’ tapes, which allowed for personalised home recordings of music (whether that was from the owner’s records or music from the radio).

This spawned ‘mixtape’ culture and a subsequent alarmist reaction by the music industry (a stand-out slogan being “Home Taping is Killing Music”). This home recording functionality of cassette recorders prompted many members of the British-Pakistani community to use them also as an audio messaging system to communicate with their relatives abroad.

Tapes were relatively cheap, re-recordable, and in many instances provided a solution to problems with literacy, in particular for many women from a lower socio-economic background who were unable to read or write letters that would have been penned in Urdu. Cassettes allowed them to record messages in their own Potwari language, allowing for their voices to be heard directly and literally.

Recordings

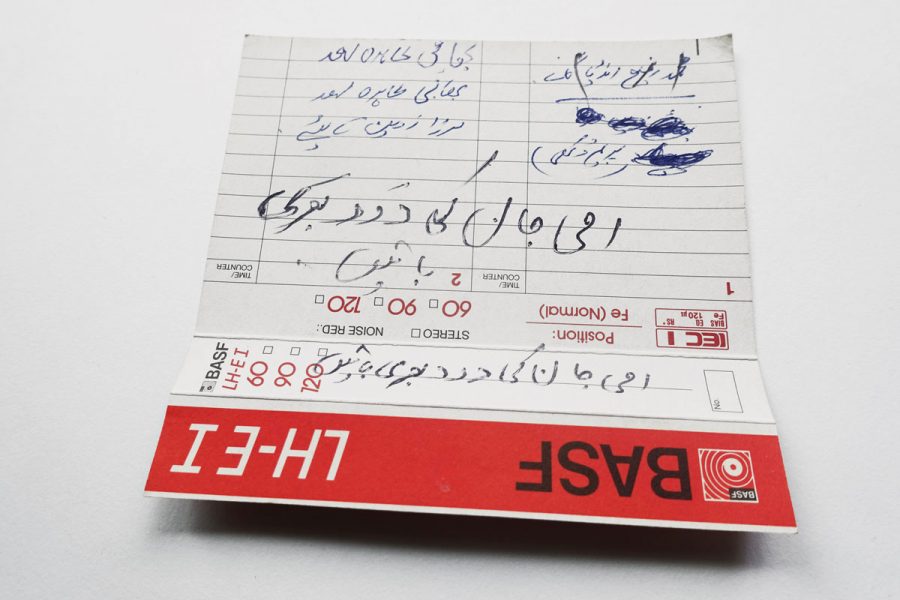

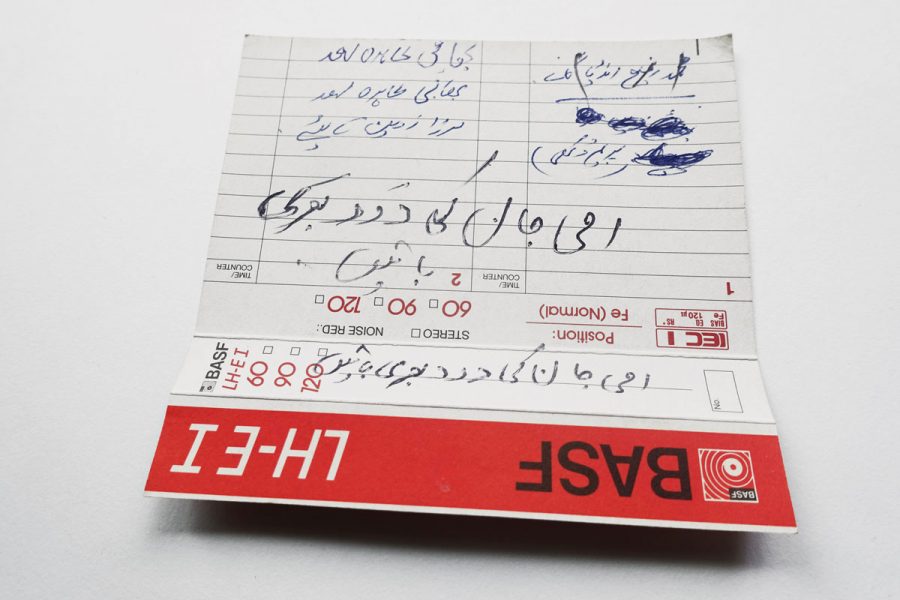

Messages were recorded on a variety of tape lengths (the most commonly used being the ‘C60’ allowing 30 minutes of audio to be recorded per side) and the cassettes were sent between families either via the postal system or they would be delivered by hand in the relatively rare instance when a family member or a trusted friend would be visiting from abroad. Cassettes would be listened to individually or collectively by the intended receivers, with messages being recorded and returned in a similar way.

By the late 1980’s however, wider technological advances in both music distribution and telecommunications made the use of tapes obsolete, and the use of cassettes as a system for messages died down.

Surviving ‘tape letter’ cassettes are quite rare as many of the cassettes that were intended for safe-keeping by older members of the community were re-recorded over by younger family members glad to have the opportunity of a free cassette.

Multiple recordings on the same cassette, with the subsequent degradation in audio quality, meant that many were rendered unlistenable and also discarded. Despite the rarity, some cassettes do exist, and the TAPE LETTERS project team have sourced a number of these surviving cassettes allowing an insight into this practice of recording messages on magnetic tape.

Some cassettes were intended for individual listening, and others for group listening. Some contained intimate messages between lovers, some contained messages between parents and their sons or daughters. Some were recorded in secret with the intention of proving culpability and used as evidence, some contained domestic chatter on the weather and an unfamiliar climate.

They all contain deeply human stories, and these ‘tape letters’ can be considered significant artefacts both as objects and as aural moments in a crucial time for the migrant Potwari-speaking community. They were recorded ‘in the moment, and of the moment’ and are fascinating sonographic snapshots, providing an unvarnished insight into private familial spheres of life at the time.

Using cassettes to communicate

Poor telecommunications networks in Pakistan and the prohibitively high cost of making phone calls from the UK at the time were a big factor, but the issue of poor literacy rates especially amongst women from a lower socio-economic background drove the practice too. Traditional gender roles for men and women in a conservative Pakistan meant limited access to formal education for many Pakistani women from poorer backgrounds. This meant that many individuals were unable to read or write Urdu – the national language of Pakistan, by the time they migrated to the UK and were essentially incapable of writing home. Very often, letters were dictated to family members but issues of privacy even between close family members prompted the use of cassettes as an alternative and parallel method to letter writing given they could be recorded alone when needed.

Background

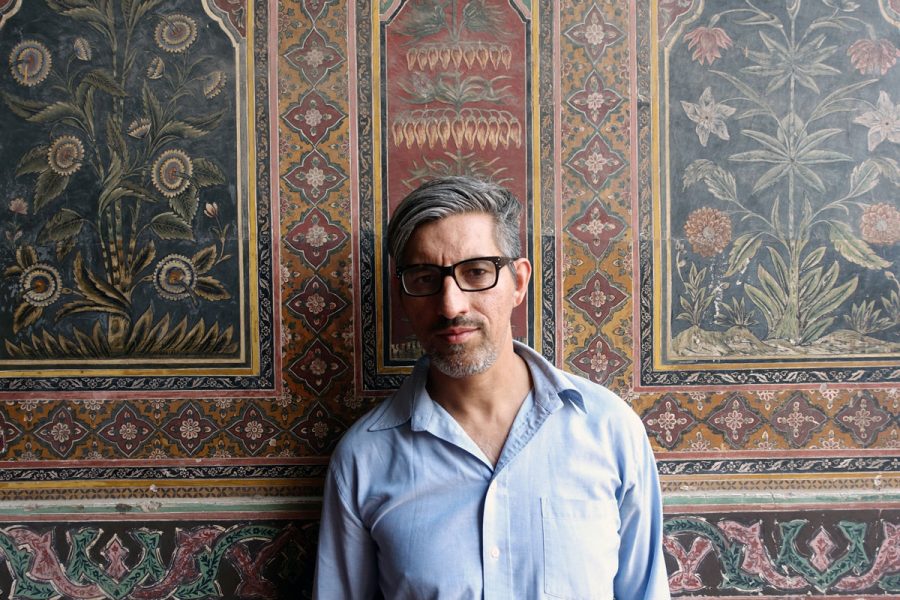

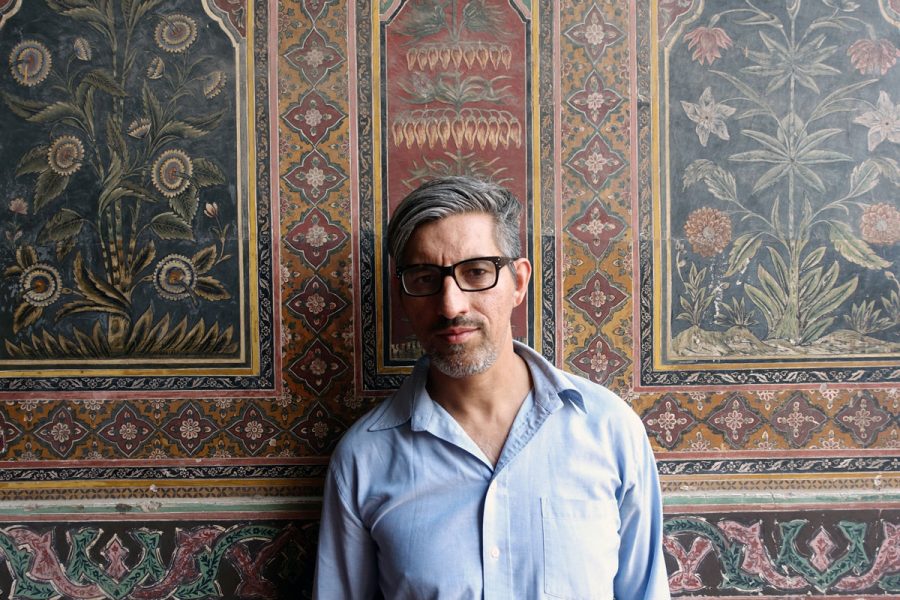

Statement by Wajid Yaseen – Director of the Tape Letters project

“Cassette tapes were an inexpensive and easy way to access and share music when I was growing up in Manchester in the 1970s, and the reaction by the music industry to home recordings on blank tapes made the illicit act of recording music off the radio or from records all the more exciting.

Like most kids, we were interested in pop music, but also rock, and new styles of electronic music coming mainly from the US (Electro and early Hip Hop) and mainland European – Jean Michel Jarre and his operatic electronica, Kraftwerk etc). Cassettes containing this music would invariably be scattered around the home, but cassettes owned by my parents would be lying around too. Their cassettes contained Ghazals (poems centring on themes of love and separation), Qawwalis (devotional Sufi music), and Naats (devotional hymns).

My father had a keen interest in Naats and very often was invited to sing in people’s homes or at public ceremonies as the British Pakistani communities in various towns and cities in the north of England settled and grew.

The development of cassette technology and the ability to record at home allowed him to share his singing within his community in an entirely new way, and a burgeoning cassette tape culture grew around his Naat singing. He passed away in 2001 but my family still have a number of these cassette recordings of him singing his Naats, and it was whilst I was rummaging around in my mum’s house a few years ago wanting to hear his voice again that I found a number of other cassettes.

The labels and inner sleeves contained scribbled messages to distant relatives and discovering them in my mum’s drawer triggered childhood memories of when I myself was coerced into recording messages to distant relatives of my own. I knew there and then that these other cassettes I’d found wouldn’t contain singing or music, but rather monologues and private messages, and by asking around, I found out that it wasn’t just my own family that used them in this way.

Given the intensely private nature of the contents of the cassettes and the obsolescence of the medium itself, I didn’t think we’d find or be given access to many of these ‘tape letters’ and indeed they are pretty rare, and when they do exist many people are understandably reluctant to share them. Nevertheless, the project team and I have managed to secure around twenty cassettes from a number of different families, and have interviewed over fifty individuals living in the UK and in Pakistan, providing us with a rich insight into this practice of recording messages on tape.

I’ve been fascinated with sound, music, and active listening since I can remember, and as I was handling these newfound cassettes in my mother’s home, I realised that these cheap pieces of plastic and magnetic tape were perfect sonographic snapshots of the time.

Reflecting and analysing them has been a sort of ‘sonic archaeology’ and the TAPE LETTERS project has provided me with an insight not only into the migratory experience of my immediate family, but also into the wider issues of migration and identity, into how language mutates and drifts, and has revealed the ingenious ways in which people adapt technology to suit their needs wherever they are, and wherever they’re from.”

Wajid Yaseen

Communication:

“It was rare to have a TV in a house, never-mind a telephone, so you know it was just a thing that if somebody was going to visit Pakistan, there’d be some excitement, ‘let’s do a cassette, and send it along’. It’d reach our relatives within a day or two as we’d give it to whoever was going to pass on by hand, and they could listen to our conversations or anything else we wanted to tell them. It was an easy way to communicate at that time.”

“People didn’t have much money so they used the same cassette over and over and over again. If I had a cassette from England or from Pakistan, I’d keep it for a while and then re-record over it and send it back. A cassette was used many many times until the quality was too bad. You could tell the quality was going down because the voice on the cassette wasn’t clear.”

Behaviours & Cassettes:

“My son Amjid got me a tape recorder and he showed me how to use it. He told me ‘mum you have to put the cassette here, switch it on here, press this button to play it, forward and backward here’. Amjid showed me all those things.”

.”

Languages:

“Hindus and Sikhs from Gujranwala (Punjab, Pakistan) and Wazeerabad (Punjab, Pakistan) were Punjabi speakers but where we are in this Gukarkhan area of Pakistan, we use the Potwari language. We and the Mirpuris (KPK, Pakistan) have the same language but other areas have different languages, like Kotli (Azad Kashmir, Pakistan) – they speak in a strange accent. But Mirpur and other areas like Pindi (Rawalpindi, Pakistan) have the same language. Peshawar is separate and in Gujranwala, the language is a little different from pure Punjabi…not much though.”

“If you couldn’t read or write and wanted to send a letter from Pakistan, you’d have to find somebody to write it for you and it was very hard especially in the villages. When you found someone who could do it, they’d give you this big attitude, ‘oh I’ll do it on a certain day, I’ll do it on that day’. It felt like begging, so instead of going to them, you’d just put your voice on a cassette and send it.”

“I only used to listen to the cassettes once or twice because I’d get upset after that.”

Relatives:

“You know when you arrive from Pakistan, you leave all your family back home – your parents, your brothers and sisters, and obviously you miss them. We used to write letters as well, but you could say more things on cassettes and in your own Pothwari language. I could tell them how much I missed them. When I came to the UK, I had some family here as well – my uncles and aunties, but when you’re away from your mum and dad and your brothers and sisters, you miss them more. I missed them so much, and I could explain all of this to them on cassettes in my own language.”

Tape Letters

The Tape Letters project shines light on the practice of recording and sending messages on cassette tape as a mode of communication by Pakistanis who migrated and settled in the UK between 1960-1980.

Drawing directly both from first-hand interviews and from the informal and intimate conversations on the cassettes themselves, the project seeks to unearth, archive and re/present a portrait of this method of communication, as practised mainly by Potwari-speaking members of the British-Pakistani community, commenting on their experiences of migration and identity, commenting on the unorthodox use of cassette tape technology, and commenting on the language used in the recordings.

The project focuses on Pothwari primarily because the majority of cassettes acquired and the majority of the interviews undertaken have been in this language, but also because it is solely a spoken language and its capture on cassette tape provides some insights into the traditions of an oral culture.

Cassette culture

Cassette tapes were developed by the Dutch technology company Phillips in 1963 originally for dictation machines, but with rapid improvements in audio fidelity, they became hugely popular as a format for pre-recorded music. They were also available as ‘blank’ tapes, which allowed for personalised home recordings of music (whether that was from the owner’s records or music from the radio).

This spawned ‘mixtape’ culture and a subsequent alarmist reaction by the music industry (a stand-out slogan being “Home Taping is Killing Music”). This home recording functionality of cassette recorders prompted many members of the British-Pakistani community to use them also as an audio messaging system to communicate with their relatives abroad.

Tapes were relatively cheap, re-recordable, and in many instances provided a solution to problems with literacy, in particular for many women from a lower socio-economic background who were unable to read or write letters that would have been penned in Urdu. Cassettes allowed them to record messages in their own Potwari language, allowing for their voices to be heard directly and literally.

Recordings

Messages were recorded on a variety of tape lengths (the most commonly used being the ‘C60’ allowing 30 minutes of audio to be recorded per side) and the cassettes were sent between families either via the postal system or they would be delivered by hand in the relatively rare instance when a family member or a trusted friend would be visiting from abroad. Cassettes would be listened to individually or collectively by the intended receivers, with messages being recorded and returned in a similar way.

By the late 1980’s however, wider technological advances in both music distribution and telecommunications made the use of tapes obsolete, and the use of cassettes as a system for messages died down.

Surviving ‘tape letter’ cassettes are quite rare as many of the cassettes that were intended for safe-keeping by older members of the community were re-recorded over by younger family members glad to have the opportunity of a free cassette.

Multiple recordings on the same cassette, with the subsequent degradation in audio quality, meant that many were rendered unlistenable and also discarded. Despite the rarity, some cassettes do exist, and the TAPE LETTERS project team have sourced a number of these surviving cassettes allowing an insight into this practice of recording messages on magnetic tape.

Some cassettes were intended for individual listening, and others for group listening. Some contained intimate messages between lovers, some contained messages between parents and their sons or daughters. Some were recorded in secret with the intention of proving culpability and used as evidence, some contained domestic chatter on the weather and an unfamiliar climate.

They all contain deeply human stories, and these ‘tape letters’ can be considered significant artefacts both as objects and as aural moments in a crucial time for the migrant Pothwari-speaking community. They were recorded ‘in the moment, and of the moment’ and are fascinating sonographic snapshots, providing an unvarnished insight into private familial spheres of life at the time.

Technology

Poor telecommunications networks in Pakistan and the prohibitively high cost of making phone calls from the UK at the time were a big factor, but the issue of poor literacy rates especially amongst women from a lower socio-economic background drove the practice too. Traditional gender roles for men and women in a conservative Pakistan meant limited access to formal education for many Pakistani women from poorer backgrounds. This meant that many individuals were unable to read or write Urdu – the national language of Pakistan, by the time they migrated to the UK and were essentially incapable of writing home. Very often, letters were dictated to family members but issues of privacy even between close family members prompted the use of cassettes as an alternative and parallel method to letter writing given they could be recorded alone when needed.

Background:

Statement by Wajid Yaseen – Director of the Tape Letters project

“Cassette tapes were an inexpensive and easy way to access and share music when I was growing up in Manchester in the 1970s, and the reaction by the music industry to home recordings on blank tapes made the illicit act of recording music off the radio or from records all the more exciting.

Like most kids, we were interested in pop music, but also rock, and new styles of electronic music coming mainly from the US (Electro and early Hip Hop) and mainland European – Jean Michel Jarre and his operatic electronica, Kraftwerk etc). Cassettes containing this music would invariably be scattered around the home, but cassettes owned by my parents would be lying around too. Their cassettes contained Ghazals (poems centring on themes of love and separation), Qawwalis (devotional Sufi music), and Naats (devotional hymns).

My father had a keen interest in Naats and very often was invited to sing in people’s homes or at public ceremonies as the British Pakistani communities in various towns and cities in the north of England settled and grew.

The development of cassette technology and the ability to record at home allowed him to share his singing within his community in an entirely new way, and a burgeoning cassette tape culture grew around his Naat singing. He passed away in 2001 but my family still have a number of these cassette recordings of him singing his Naats, and it was whilst I was rummaging around in my mum’s house a few years ago wanting to hear his voice again that I found a number of other cassettes.

The labels and inner sleeves contained scribbled messages to distant relatives and discovering them in my mum’s drawer triggered childhood memories of when I myself was coerced into recording messages to distant relatives of my own. I knew there and then that these other cassettes I’d found wouldn’t contain singing or music, but rather monologues and private messages, and by asking around, I found out that it wasn’t just my own family that used them in this way.

Given the intensely private nature of the contents of the cassettes and the obsolescence of the medium itself, I didn’t think we’d find or be given access to many of these ‘tape letters’ and indeed they are pretty rare, and when they do exist many people are understandably reluctant to share them. Nevertheless, the project team and I have managed to secure around twenty cassettes from a number of different families, and have interviewed over fifty individuals living in the UK and in Pakistan, providing us with a rich insight into this practice of recording messages on tape.

I’ve been fascinated with sound, music, and active listening since I can remember, and as I was handling these newfound cassettes in my mother’s home, I realised that these cheap pieces of plastic and magnetic tape were perfect sonographic snapshots of the time.

Reflecting and analysing them has been a sort of ‘sonic archaeology’ and the TAPE LETTERS project has provided me with an insight not only into the migratory experience of my immediate family, but also into the wider issues of migration and identity, into how language mutates and drifts, and has revealed the ingenious ways in which people adapt technology to suit their needs wherever they are, and wherever they’re from.”

Wajid Yaseen

Communication:

“It was rare to have a TV in a house, never-mind a telephone, so you know it was just a thing that if somebody was going to visit Pakistan, there’d be some excitement, ‘let’s do a cassette, and send it along’. It’d reach our relatives within a day or two as we’d give it to whoever was going to pass on by hand, and they could listen to our conversations or anything else we wanted to tell them. It was an easy way to communicate at that time.”

“People didn’t have much money so they used the same cassette over and over and over again. If I had a cassette from England or from Pakistan, I’d keep it for a while and then re-record over it and send it back. A cassette was used many many times until the quality was too bad. You could tell the quality was going down because the voice on the cassette wasn’t clear.”

Behaviours & Cassettes:

“My son Amjid got me a tape recorder and he showed me how to use it. He told me ‘mum you have to put the cassette here, switch it on here, press this button to play it, forward and backward here’. Amjid showed me all those things.”

Languages:

“Hindus and Sikhs from Gujranwala (Punjab, Pakistan) and Wazeerabad (Punjab, Pakistan) were Punjabi speakers but where we are in this Gukarkhan area of Pakistan, we use the Potwari language. We and the Mirpuris (KPK, Pakistan) have the same language but other areas have different languages, like Kotli (Azad Kashmir, Pakistan) – they speak in a strange accent. But Mirpur and other areas like Pindi (Rawalpindi, Pakistan) have the same language. Peshawar is separate and in Gujranwala, the language is a little different from pure Punjabi…not much though.”

“If you couldn’t read or write and wanted to send a letter from Pakistan, you’d have to find somebody to write it for you and it was very hard especially in the villages. When you found someone who could do it, they’d give you this big attitude, ‘oh I’ll do it on a certain day, I’ll do it on that day’. It felt like begging, so instead of going to them, you’d just put your voice on a cassette and send it.”

“I only used to listen to the cassettes once or twice because I’d get upset after that.”

Relatives:

“You know when you arrive from Pakistan, you leave all your family back home – your parents, your brothers and sisters, and obviously you miss them. We used to write letters as well, but you could say more things on cassettes and in your own Pothwari language. I could tell them how much I missed them. When I came to the UK, I had some family here as well – my uncles and aunties, but when you’re away from your mum and dad and your brothers and sisters, you miss them more. I missed them so much, and I could explain all of this to them on cassettes in my own language.”